The Persian Parrotia

By Walter Reins

ISA Certified Arborist®

November 19, 2024

A Persian parrotia tree (Parrotia persica)

For a variety of reasons, there are certain trees that never seem to get the attention and use they deserve in our Ohio landscapes. The Persian parrotia is one of those trees. The landscape industry tends to rely heavily on a narrow variety of tree species and the Persian parrotia is often overlooked when considering planting options for the landscape. Let’s shed some light on this beautiful, adaptable, and underutilized option.

The Persian parrotia (Parrotia persica), also sometimes known as the Persian ironwood, is a deciduous tree native to a small range of temperate forests in the Middle East. It can grow up to around 30 feet in height with a mature width of 15 to 30 feet. The crown’s shape is generally round or ovular and you may encounter trees grown with either single or multiple stems. The mature size of this tree alone makes it a noteworthy species as this medium size at maturity is often hard to come by and is typically satisfied with trees like river birch or linden. The former often has major health issues with central Ohio’s urban soils. Parrotias tend to be tolerant of less than ideal soil conditions once established, making them a good choice for residential, commercial, and municipal landscapes. Consideration should still be given to location on any property with regard to overhead wires as a 30 foot tree may still be tall enough to interfere with these utilities.

Fall color of Persian parrotia. Note the ~4 different colors of its leaves!

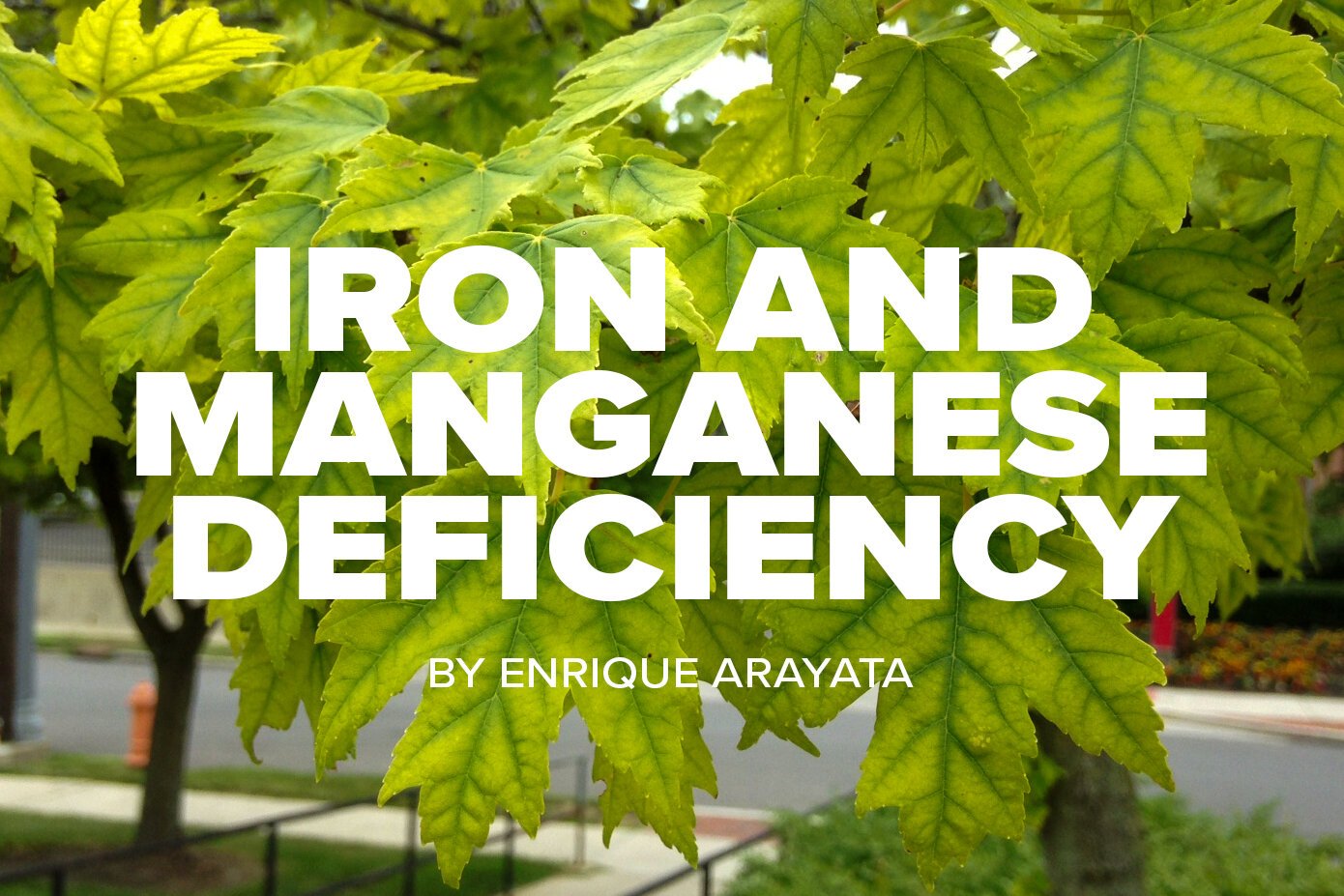

In addition to a desirable size as an accent or shade tree in the landscape, parrotias feature attractive dark green foliage with a gentle serration along the leaf margin. Avid gardeners and tree enthusiasts may find that parrotia foliage resembles that of witch hazel and fothergilla. This is because all three of these species belong to the witch-hazel family (Hamamelidaceae). Fall color is among the best you can find, with blends of yellows, oranges, pinks, and reds that almost seem to glow at the peak of fall foliage season. After the leaves drop, the tree continues to provide winter interest with a beautifully smooth and mottled bark, not unlike the mature bark of crape myrtle or lacebark pine. Flowering in central Ohio occurs in late winter and is not particularly showy. Parrotias are cold hardy to zone 4 (5a), making it a great match for central Ohio winter temperatures.

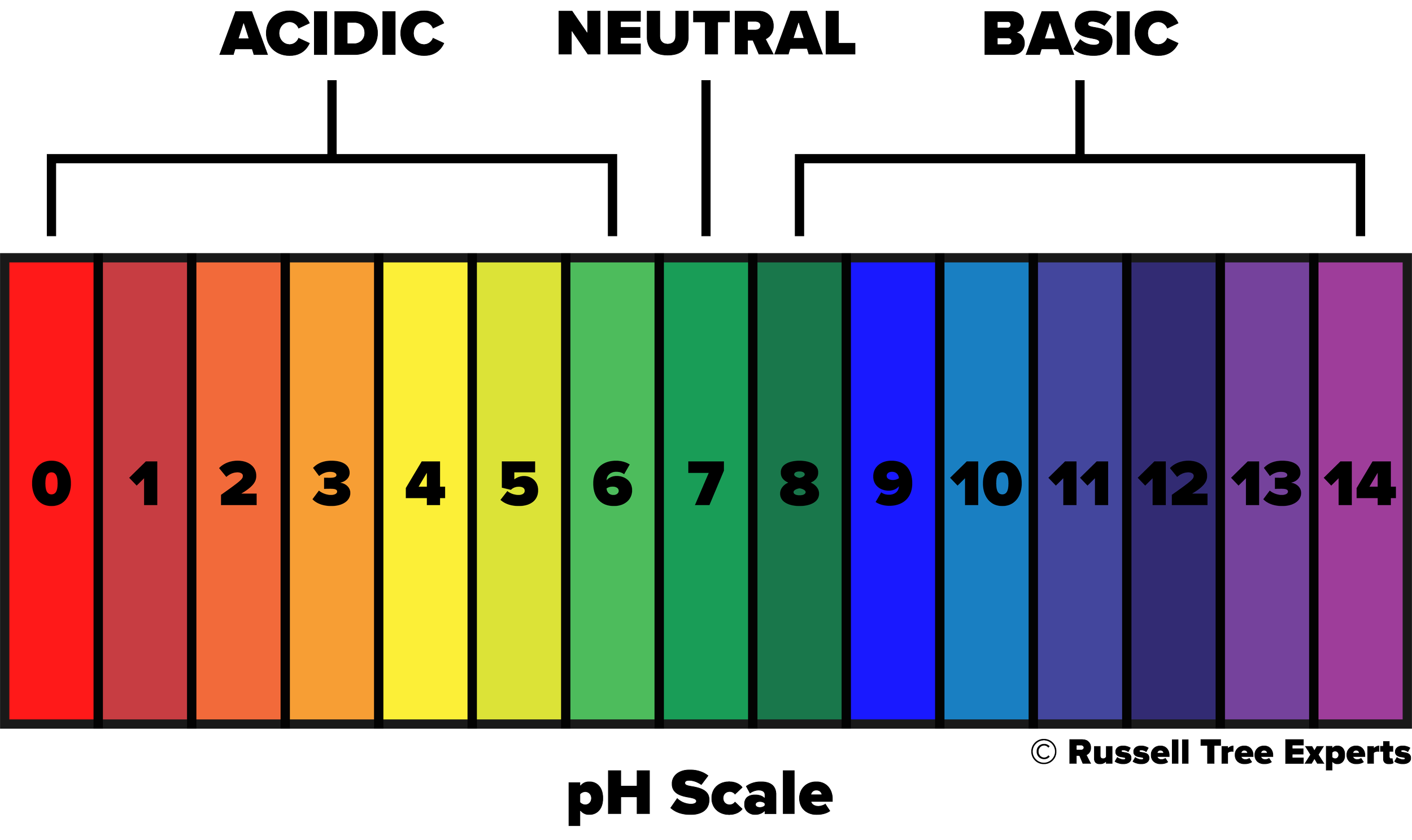

When planting a parrotia, the selected site should receive full sun to partial shade. Even though the species is tolerant of a variety of soil conditions, including soil pH and somewhat poor soil structure, the site should be well drained and not prone to standing water. With proper location to accommodate its future mature size, correct planting methods, and aftercare, parrotias can be healthy and beautiful additions to an Ohio landscape for several or more decades. Best of all, they are readily found at Ohio plant nurseries and garden centers, making them a tree species that you shouldn’t have to go too far to find! Happy planting!

ADDITIONAL ARBOR ED ARTICLES!

Sincerely,

Walter Reins I Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Walter became an ISA certified arborist in 2003 and has a degree in landscape horticulture. He has 25 years of experience in the tree and landscape industries and originally began working at Russell Tree Experts in 2011. Walter is also the owner/operator of Iwakura Japanese Gardens, a small design/build/maintenance firm specializing in Japanese-style gardens, and also offers responsible tree planting for all landscapes.