By Chris Gill

ISA Certified Arborist®

May 23, 2024

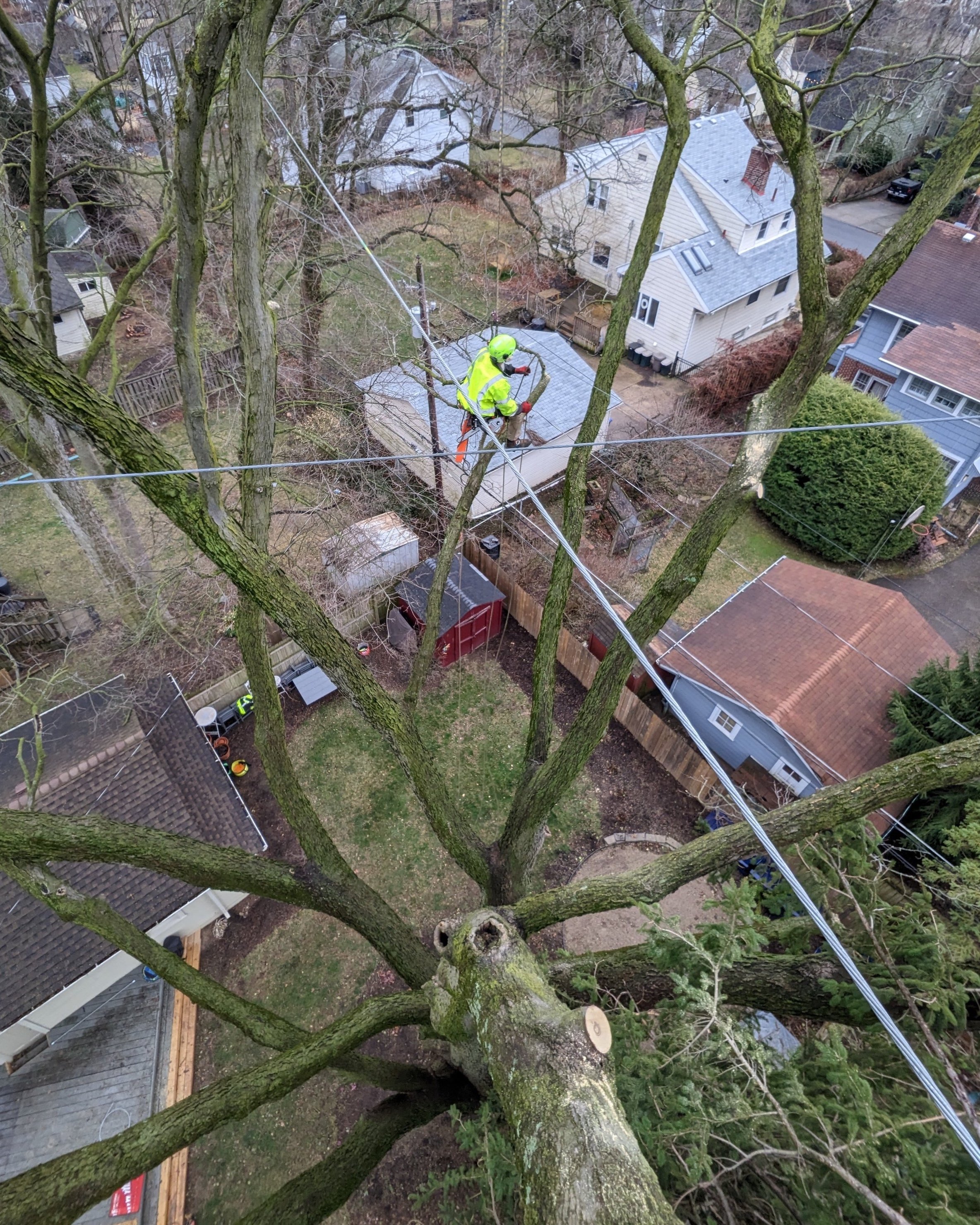

A bagworm on a Colorado blue spruce tree (Picea pungens)

Bagworms are a serious pest to a variety of ornamental plants in our landscapes. Bagworms are the caterpillars of a moth. These caterpillars are called “bagworms” because they wrap themselves in a bag constructed of material from their host plant. The bags camouflage the bagworms from predators as they feed and can also make effective treatments challenging. Understanding their life cycle, preferred host plants, feeding habits, and effective treatment methods are crucial for managing infestations and preserving the health of your plants.

Life Cycle of Bagworms

Bagworms undergo a fascinating life cycle, transitioning through various stages from egg to adult moth. Let’s start with the hatching of the eggs and the main feeding stage. This is the stage that is the most noticeable and damaging to the host plant. Starting in early June into July, the larvae emerge hungry and begin constructing their protective cases using silk and surrounding plat materials. As they feed on foliage, they expand and reinforce their bags, incorporating leaves, twigs, and other debris to camouflage themselves and deter predators.

After reaching maturity, which typically takes several weeks, the larvae stop feeding and prepare for pupation. Within the safety of their bags, they undergo metamorphosis, and the males emerge as adult moths and the female bagworm remains in the bag for mating. Once mated the female bagworm lays her eggs and their life cycle is over at this point. There can be as many as 500-1000 eggs. The eggs overwinter inside the dead female's bag and the cycle begins again in the spring.

Feeding Habits

The larval stage of bagworm is the main feeding stage, consuming foliage from their host plants as they construct their protective bags. This feeding stage can last several weeks to a couple of months depending on environmental conditions and the availability of food sources. They use their silk threads to anchor themselves to branches or leaves, where they remain while feeding. As they consume foliage, they gradually defoliate the plant, weakening its overall health and potentially causing significant damage if left untreated. Complete defoliation often leads to plant death. Once the bagworm reaches maturity, they quit feeding and focus on mating.

Main Host Plants

Bagworms are known to infest a wide range of host plants. Some of the most common host plants for bagworms include:

Evergreens: Arborvitae, juniper, cedar, pine, spruce, and cypress are often targeted by bagworms, which can cause severe damage to these trees if left unchecked.

Deciduous Trees: Bagworms may also infest deciduous trees such as honey locust, oak, maple, sycamore, willow, and poplar, feeding on their leaves and weakening the overall health of the tree.

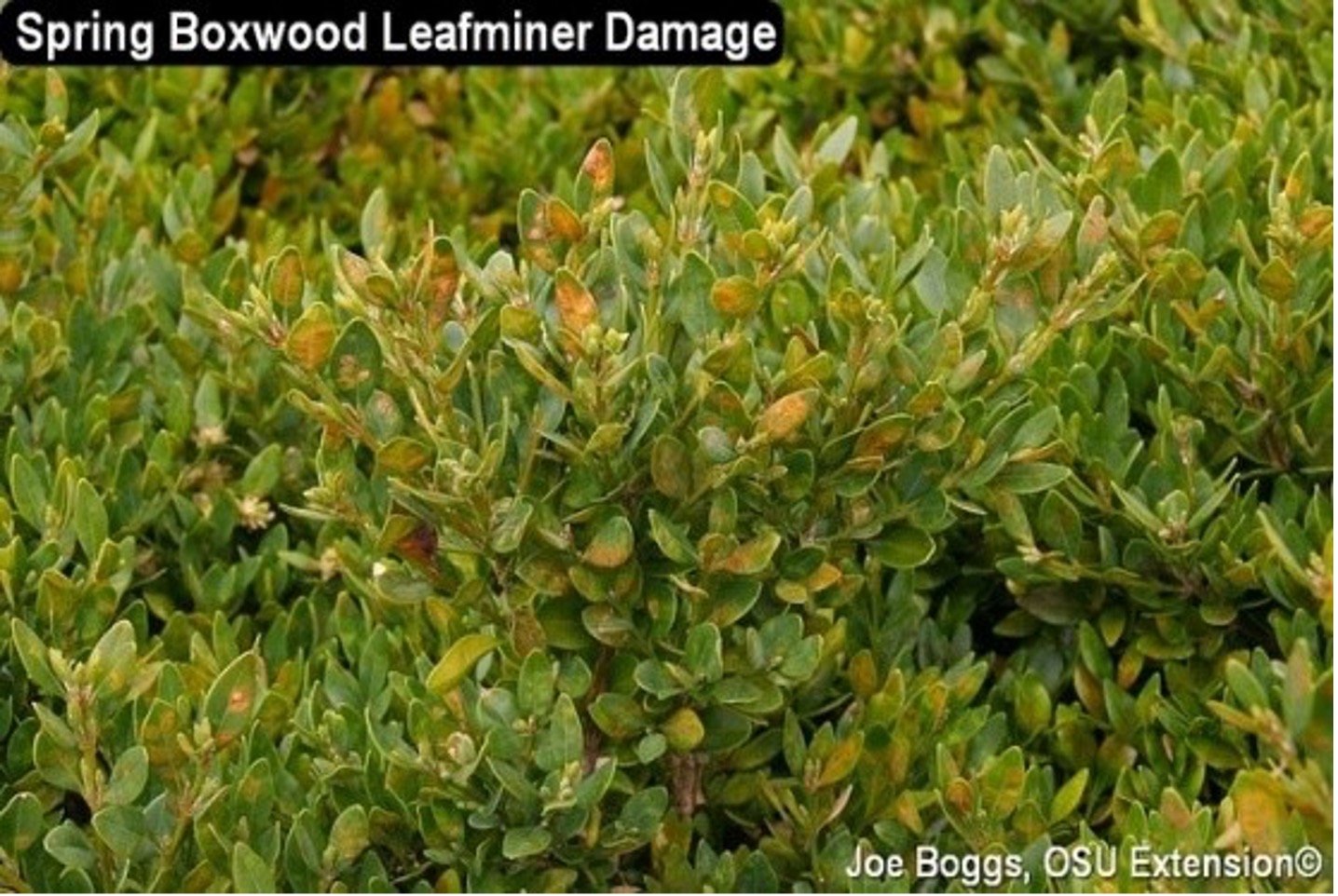

Ornamental Shrubs: Boxwood, azalea, holly, and other ornamental shrubs are susceptible to bagworm infestations, which can defoliate and disfigure these plants if not addressed promptly.

While bagworms are adaptable and may infest various plant species, their preference for evergreen trees is most common.

Treatment Options

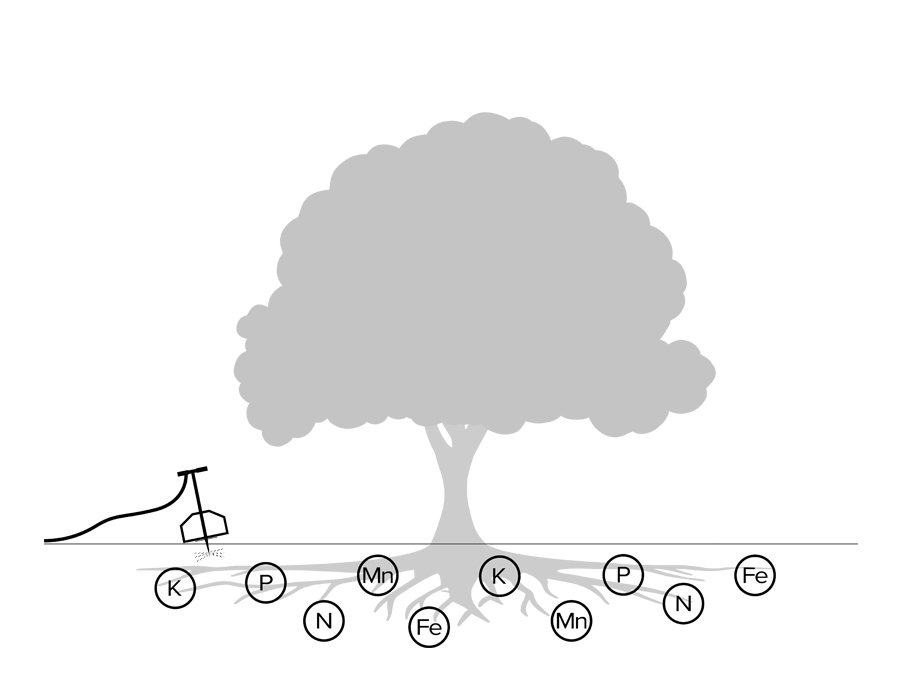

Managing bagworm infestations can be done in a few ways - culturally, mechanically, or with chemical control methods. The most effective strategy will depend on the severity of the infestation and the size of the plants that are being treated. The following are some effective strategies for treating bagworm infestations:

Handpicking: In smaller infestations, manually removing bags from affected plants can be an effective control method. Simply pluck the bags from the branches and dispose of them properly to attempt to prevent future infestations. You can throw them in the trash or burn them.

Biological Control: Introducing natural predators of bagworms, such as parasitic wasps, or predatory insects, can help reduce populations naturally without the need for chemical intervention. (Flowers with lots of nectar can attract these predator insects). I like this method but do not recommend relying on it for managing heavily infested plants.

Insecticides: Applying two well timed insecticide sprays spaced two weeks apart has been the most effective way to control bagworms. Applying the product early while the larva is feeding and in the initial stages of making their bag is essential. Once they have constructed a bag around their bodies, insecticides are far less effective.

- - -

Bagworms may be small but their impact on plants can be quite serious. The damage is not obvious early in the season because the caterpillars and their bags are small, and the bags can be difficult to see until large numbers are present. Bagworms often are not detected by the untrained observer until August after severe defoliation has occurred. Getting to the plants early and detecting a problem can save a lot of headaches. At Russell Tree Experts we are trained to spot bagworms and use the OSU phenology calendar to properly time applications for effective control.

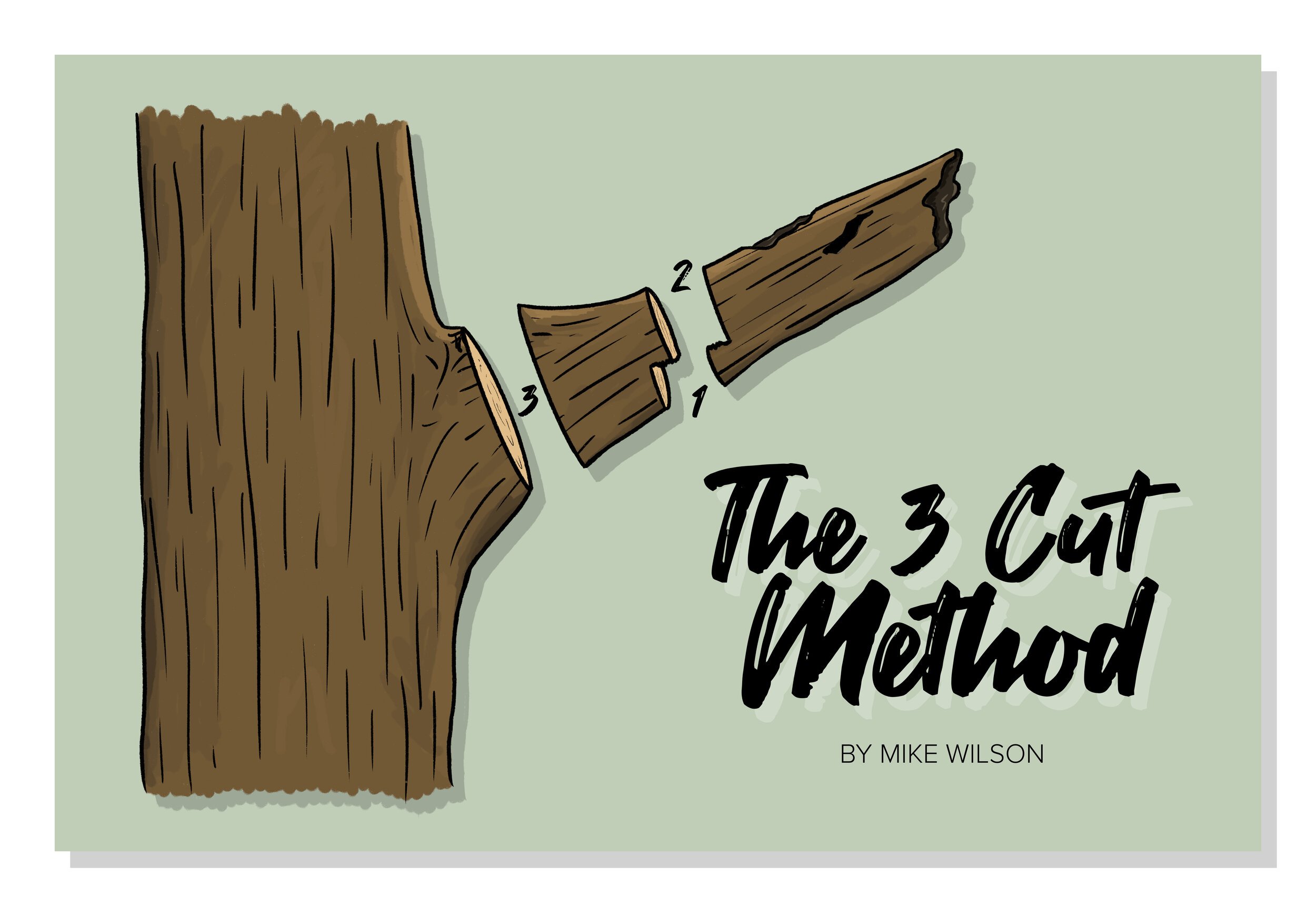

Additional Arbor Ed Articles!

Tree Preservation Videos!

Sincerely,

Chris Gill I Regional Manager, Russell Tree Experts

Chris joined Russell Tree Experts in 2015 and has been in the green industry for over 15 years. When not at RTE, he enjoys spending time with wife & son, wakeboarding, and hunting. His favorite trees are the white oak & sugar maple for their beauty and uses beyond the landscape. Chris is an ISA certified arborist, EHAT certified, CPR and first aid certified, holds an ODA commercial pesticide license, and holds a tree risk assessment qualification (TRAQ).